|

Movement I

Listeners accustomed to the

modern technique of recording generally do not understand why Toscanini

insisted so persistently on the dampened, echo-less acoustics of NBC’s

Studio 8H. (Toscanini’s will continued to prevail in the early 1950’s,

when one of the record company’s engineers wanted, in the interest of ‘euphony’,

to touch up his Beethoven recordings with artificial reverberations. The

records had to be called back). His justification for this almost qualifies

as an artistic confession. He was only willing to work under such acoustic

conditions in which every element of the music was ‘clearly audible’. It

is no coincidence that Bruno Walter chose an echoing riding school for

the scene of his later recordings, the reverberating sounds of which embraced

the orchestra with soft and even euphony. For Bruno Walter worked with

a broad brush, while Toscanini drew with a sharp steel blade. Walter’s

recordings were like an impressionistic photograph, prepared with the help

of a ‘blurring lens’, whereas in Toscanini’s recordings even the finest

details must be seen clearly. He put reality of feeling and exactness of

form before aurally gratifying euphony. It is interesting that even a mediocre

record-player gives a more or less acceptable picture of the Olympian proportions

of Klemperer’s rhythms, Furtwängler’s demonic dynamics or Bruno Walter’s

dreamlike agogics, because the changes in the acoustical sphere – the musical

character changes – take place relatively slowly, allowing our ears

to follow them more easily. It is not so with Toscanini. If, as a result

of weakness in the playing-back of sounds, the infinitely nuanced drawing

of the musical formation becomes blurred, the musical intentions will,

together with it, also remain in obscurity. Just as Leonardo’s Mona-Lisa

would lose its magic if we were to know it from a picture in a daily paper,

a mediocre musical reproduction is unable to represent Toscanini’s ideas.

The tangible perceivability of the instruments and the clear soundscape

were for him the essentials of every musical performance.

He was well aware of the

reasons. His musical dramaturgy, one of the most characteristic traits

of his orchestral art, was realized by the qualitative changes in

the tone. (However unbelievable this may seem: in the case of an ideal

reproduction, next to the tone of the Toscanini-orchestra, recordings prepared

using a much more advanced procedure seem also to be more monotone – they

awaken a more one-sided impression.) There was hardly anyone among his

contemporaries who was more perceptive of the form of the music in the

momentary transformations of timbre, or who would have attached so much

importance to the difference between quantitative and qualitative elements

of expression; that is to say, between dynamics and color.

Perhaps no one knew better than him the value of the moment (or

rather the value of the event that occurs at that moment). The meaning

of tonal colors; their rapid changes similar to human speech – if one may

say, the ‘articulation’ of color – formed the basis of his musical phraseology.

He demanded the same of his players, just as he demanded perfectly clear

diction from his singers.

The clarity of the ‘consonants

and vowels’ of the orchestral timbre – the volubility of the tonal picture

– appears immediately in the signature theme of the symphony that

we are to examine: Toscanini shades the initial a-e step of the

oboe with no less than four timbre changes. We should rather write the

smooth half-notes of the motive as:

Neither the resonant background

of the short forte and long piano chords nor the motivic

inversion (the reflection of the fourth) alone gives the reason for the

unveiling of the ‘active’ and ‘passive’ face of the pair of bars – the

reason lies much deeper. This must be approached through a bit of a detour.

The basic form of a classical

melody, as we know, is the period – the melody usually falls symmetrically

into 2+2, 4+4 and 8+8 bars. (To the ‘question’ of the first two bars, the

subsequent two bars give an ‘answer’, the thus unified four bars can nevertheless

be seen as a single question, to which bars 5–8 now give an answer. The

form continues to develop in a similar manner: the eight bar period ends

in a half cadence and rhymes with the resolution – the authentic cadence

– of the sixteen bar period.)

There is, however, a characteristic

and frequent type of melody found in Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven that allows

a deeper view of the proportional laws of the classical theme. (One is

amazed that the following order has thus far escaped the notice of musicologists.)

In the characterization of

this type of melody, we must view as the ‘unit of measurement’ that meter

in which we should have to conduct the melody (or in which an ideal conductor

would conduct it). The smallest motivic component comprises four beats

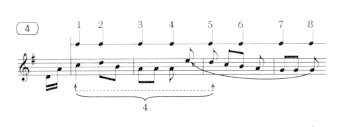

arranged in such a manner that the tension point 2)

touches the beginning of the second beat, which means that this tension

point actually appears in order to determine the value of the ‘unit

of measurement’:

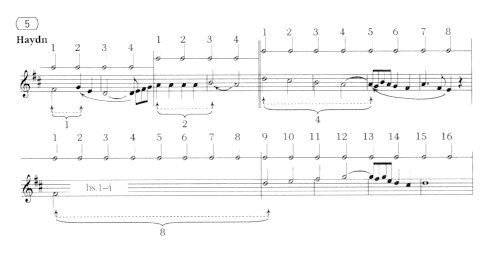

There is no more need to

determine the value of the ‘unit of measurement’ in the following four-beat

group – the place of the tension point shifts. Not one, but two

units of time elapse before it reappears, since the form itself has grown

twofold:

The melody continues to develop

logically along the same principle: a newer 8 beats answers the already

measured 8 beats, meaning that we must now take a four-step, rather

than a two-step path to the tension point:

For the sake of completeness,

let us also cite a period consisting of 32 units of measurement. In the

second half of the melody, as expected, not four, but eight units

of value determine the position of the tension point (indeed, after the

unchanging repetition of bars 1–4, something new occurs in the 13th

bar of the second half period):

In summary, along with the

periodic growth of the melody (4–8–16–32), the tension point also undergoes

a gradual shift (by 1–2–4–8 units).

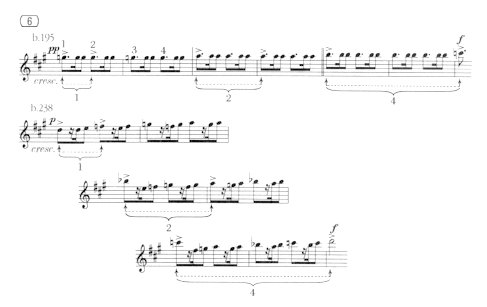

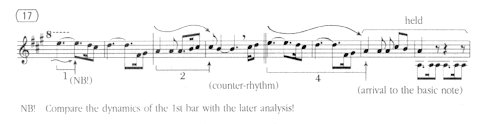

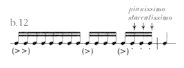

The extent to which the dynamic

qualities of this theme structure can be used to create tension is shown

by the following two examples of intensification from the 1st

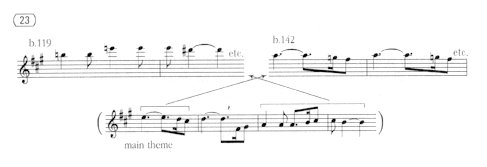

movement in Toscanini’s recording 3):

Returning now to our starting

point, let us prepare an ‘electrocardiogram’ of bars 1–2 by breaking down

the dynamic and color components of the sound:

What is happening on the

second eighth? The oboe’s sound throbs with pain after the forte

stroke and the short, whip-cracking chord of the orchestra. The opposite

can be seen, on the other hand, from the last fourth of the bar: the oboe’s

timbre changes captivatingly (a touch of bliss is concealed in that change),

as if the performer had changed unnoticed to a softer-colored instrument,

thus preparing the easing of the second bar. The splendor (I cannot find

a better word for this) that accompanies this relaxation is the first great

event of the performance. It is also the first lesson, for we buy this

event at a price: the first bar’s burst of pain makes the relaxation of

the second bar possible. It is just the unity of the principles

of tension and joy that preserves this event from all elements of romantic

eroticism.

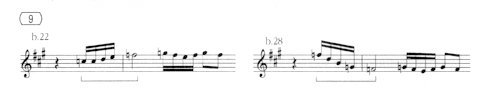

In the two Haydn excerpts

we can observe that the tension point ‘steps out’ from the preceding events

and connects to the consequent element of the motive:

(that is to say, it is not

so much with the antecedent, but rather with the consequent that the tension

point forms a magnetic unit). For this reason we divided our signature

theme into two layers. We must imagine the timbre changes of the second

eighth and the fourth quarter as if new instruments were stepping out of

the score and were melodically stringing the melody line to the next

note (see the arrows of Fig. 7).

The relaxed state of the

melody (in the middle of bar 2) multiplies the intensity of the forte

shaking that follows. It is thus that this music born of explosions

results in Beethoven’s most effective ‘music of creation’, or musica in

nascendi. According to Toscanini’s interpretation, the melody must cry

out with pain because the forte shaking has woken it from some kind of

sleep beyond dreams, and when it wishes to slip back into unconsciousness,

the stroke repeats itself again and again in order to prod the melody back

to life. This is the deeper meaning of the tension and absence of

tension in the theme. It is in this birthing-thought, however, that Toscanini’s

interpretation (not only here, but also in the case of the second theme)

strays from the traditional understanding, which holds – and here we can

quote Schumann – that this introduction ‘announces the celebration’. Toscanini

lives through every pain and jolt of birth in contrast to his usual, ceremonial

intonation 4).

Nevertheless, bar 7 is the

real touchstone of the musical logic that nearly mirrors natural laws;

it is the breakwater of the structure 5).

The basic rule of this style of expression is that on ‘this’ and on the

‘other’ side of the peak, inverted regularities and opposing attractions

in form become valid. (Toscanini is also justified by the outward appearance

of the score, since the relation between the ‘active’ odd and the ‘passive’

even measures reverses in bars 9–14). After the breakwater of bar

7, bar 8, rather than being eased, is made more and more troubled. Yet

after the gradually heavier-growing chords of the strings 6),

a momentary breath enters, and in the place of the earlier explosions

(in the odd bar 9), there follows the s o l u t i o n. I would like to

express here the true, living significance of this concept that has become

clichéd over the course of time: the fundamental point of Toscanini’s

‘ars poetica’ may be that there are no empty, worn-out modes of expression

and faded or threadbare musical clichés – the creative power is

enthralling in the way that each of the seemingly cooled musical formulas

is brought to new life, returning the phrases that have become conventional

to their original, untamed raw and powerful states. In bar 9, the heartbeat

of the music stops at a motion from Toscanini, and an indescribable easing

spreads over our ‘limbs’. There is no such Tristan-like softening; no romantic

appeal to death (‘ancestral oblivion’) 7),

that could attain this point with such an effect. Toscanini, however, as

we have said, knows the value of the ‘moment’: the easing only lasts for

a few moments so that subsequently a light cloud arises from it in bar

10 8).

After the condensed action

of the opening measures, bars 15–22 build with monumental rocks. The chords

of the wind instruments, as the score also shows, create a cohesive

force between the odd and the even bars. The sustained chords of the odd

bars strain towards the muffled beats of the even bars. The difference

between, on the one hand the sustained, tense character, and on

the other hand, the beat-like, explosive character of the intonation

(that is, of the ‘linear’ and the ‘partitioning’ elements) will be one

of the key questions of our stylistic examination. Only the slower tempo

differentiates bars 34–41 from the earlier fortissimo section: the wilfully

shortened endings – ‘fist-raisings’ – of bars 34–36–38 plunge into bars

35–37–39 with a dull beat.

In the last bars of the fortissimo

blocks (bars 22 and 41) this anger ‘evaporates’ without a trace. The staccatos

of the scale motive are airily and nimbly becoming light (like at bar 10)

and are flung into a weightless state. This is already the forest of Ariel

and Puck, and this evocation of a ‘fairyland’ belongs among the most enticing

of Toscanini’s ‘pleasurable experiences’. It is as if the glittering incorporeality

and weightlessness were that dimension, in which his lively spirit flutters

around the most at home. In fact, this scale motive could serve as an example

that one single, seemingly unimportant difference in phrasing can change

the entire order of the elements of form. According to the conventional

understanding, the new melody is born in bar 23, while in Toscanini’s

interpretation, it arises four sixteenths earlier. Thus the scale motive

can rush into bar 23 with a single swoop, and the half note (f)

pops up unexpectedly in front of us ‘in amazement’ – not in ‘emotional’

tension, but rather in ‘sensuous’ color.

Incidentally, three short

remarks will be inserted here:

1. The oboe melody begins in the score as well with four sixteenths run

(see Fig. 9).

2. The 4 sixteenths lead (in the violins) at the end of bar 28 fully supports

Toscanini, making an appearance with similar logic.

3. We also receive an answer

as to why Toscanini exposed the analogous sixteenths in bar 9 so resolutely

(to which the playful decrescendo of the peak of the scale effectively

replied):

As we mentioned, the maestro

also places the second theme in the service of the ‘birthing’ thought,

and thus tears himself fundamentally even further from the conventional

conception. After the intensely singing, melodically saturated odd bars

(23, 25), almost every conductor would handle the even bars (24, 26) merely

as minor components or afterthoughts, with the help of which the motif’s

form can be rounded off. Toscanini, however, on the basis of the score,

restores the melody’s original accentuation; that is, facing the passive-sensuous

magic of the first bar, he restores to right the active-rhythmical

tension of the second bar:

In fact, Beethoven also does

this when he emphasizes the characteristic rhythms of the even bars,

in order to make them distinct in the ostinato of the viola (these are

made even more contoured in bars 43 and 45). With this Toscanini unveils

one of the most important motifs of the introduction: in that rhythm lies

the basic motion – the basic rhythm – of the composition, which

follows through the four movements of the symphony (cf. Fig. 106). It means

nothing less than that in this rhythmic motion we can observe moments of

the conception of the piece. Toscanini’s interpretation compellingly desires

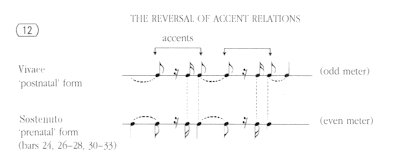

that we imagine the rhythm of the Vivace next to this rhythm:

The two rhythms relate to

each other as if they were of the same thought; as if the two facades

of night and day, underground and above ground – Hades and Olympus – were

to face each other. The two formulas are mirror images of each other 9),

and this duality unfailingly affects us like the basic motion’s ‘prenatal’

and ‘postnatal’ form – a latent ‘Hades’ and a sun-flooded ‘Olympus’. (In

bars 60–66, with the metamorphosis of the rhythm, we can peek at the moment

of birth.)

With this interpretation,

namely, with the activation of the even bars, Toscanini creates order in

a different sense, too. This motion (bar 24) is no other than the continuation

of the symphony’s signature theme – the opening theme. The opening

theme connects a downward and an upward stepping motion to each other (a-e

and c# -f#). The above mentioned motion merely changes the elements

of the melody:

The interval of the fourth

(at the end of the motive) becomes so expressive with Toscanini, because

it rhymes in a natural manner with the opening step of the symphony. 10)

(This is caused by the sudden ‘burst’ of the c-g melody arch of

bar 24 and the gesticulating effect of the condensed rest after the 2nd

quarter, together with the suddenly high-leaping g-c fourth’s sharp rhythm).

That Beethoven also intends such a role for it is evident from bar 28,

where, almost as the ‘punch-line’ of the theme, this fourth interval steps

forward unexpectedly in the violins. Our recording illuminates this moment

with exceptional sharpness 11).

Behold! What complications

and ramifications there are that Toscanini simply calls ‘faithfulness

to the score’. However, it contains no fewer problems than the formation

of the opening bars of the theme.

In contrast to that intractable

opinion that Beethoven’s works can necessarily only be properly interpreted

by German conductors, we must assert the counterexample – that German conductors

frequently misinterpret the French influences that crop up all over in

Beethoven’s music, such as sensuous-color elements, acoustic effects, and

elements of intonation. The French influence accompanied Beethoven through

his entire life. Early on he became acquainted with the works of Méhul,

Dalayrac, Grétry, Gossec, Kreutzer, Gaveau and Monsigny. Moreover,

he considered Cherubini, and not Mozart, to be the greatest opera composer

of the age (he heard some seven of Cherubini’s operas and took notes for

himself on some of the scenes of The Water Carrier). He employs

the French influence, for instance, in the harp in the ballet music Prometheus.

He received an abundance of influences from Gluck’s operas, and above all,

through his tutor, Neefe. His contemporaries already take note of this

influence (Hoffmann, later Wagner himself mentions it; cf. Schmitz, Thayer

and R. Rolland’s relevant publications). His birthplace, Bonn, due to its

geographical location is a French-spirited cultural territory. From his

years in Bonn on, his fantasy was occupied by the questions of color and

painting. Among other works, he was familiar with the study on the art

of painting in music by the contemporary writer Engel. Nothing shows his

ideas on acoustics better than a diary-entry from 1823: ‘If a thought occurs

to me, I always hear it on some instrument…’

By way of explanation, let

us add to this that the ‘sensuous’ and ‘emotional’ contents of the sounds

differ mainly in that the sensuous elements originate in real perception

– from the outer, direct effect of the sound. The emotional elements,

on the other hand, are invisible, since their effect is expressed through

the inner dynamics of the emotions (in this, they carry an irrational content:

they are not directly ‘palpable’). It is no coincidence that the emotional

world of expressionism found its true home in Germany, while sensuous impressionism

was at home in France.

One of the chief virtues

of Toscanini’s interpretation lies in the fact that he creates an ideal

balance between the tonal elements of French and German origin. In the

case of the recent theme (bar 23), he contrasts the 1st and

3rd bars, with their sensuous color-effect, to the rhythmical

strength of expression of the 2nd and 4th

bars. In this, the score once again supports him. Beethoven writes, obviously

for coloring purposes, a violin pedal-point over the 3rd

bar that pulls a magic color curtain above the melody. (Most likely, the

majority of conductors would interpret the melody differently, if one were

to imagine this g-pedal-point over bar 23 as well – how well the

sensuous violin position of bar 25 thus rhymes with the naive wonderment

of bar 23.)

The melody line itself (bars

23 and 25 f-g-f-e-f-g-f), however, was born to be painted. With

the help of a written-out ornament, it colors around the f, returning

the original, coloring meaning to the ornamentation, not to mention that

the f, as overtone (‘natural seventh’), is color itself.

If we were to grasp the event

by the roots, we would have to say that the significant material of the

odd and even numbered bars moves on paths going in the opposite direction

(as if the sounds themselves were progressing in the reverse direction):

the impressions of the 1st and 3rd bars arrive from

outside

– just like the pictures of a natural phenomenon. The tense motions of

the 2nd and 4th bars, on the other hand, rise from

inside (the ‘source of sound’ of the former is outside, while that

of the latter is inside us). We ‘notice’ the one, gazing intently at it,

while we intensively ‘want’ the other.

All in all, the Toscanini

performance casts light on the correlation of content and form, as cannot

be acquired from any composition handbook nor from any study on aesthetics.

The secret of Toscanini’s stern greatness and spiritual strength is that

he judges the characters of the individual thematic forms from the

entire

form – he always derives the details from the entirety of the work, and

does not have the whole follow from the details. (We know that he never

yielded to the temptation of momentary impressions and always made fun

of those conductors who conducted to the ‘public’ or melted every time

they reached a ‘beautiful’ passage.) Toscanini mercilessly sacrificed all

outside effects for the sake of artistic truth. This is why his way of

performing awakens the impression that superhuman powers are manifesting

themselves in him.

If we listen to Bruno Walter,

it appears even involuntarily as if ‘we were talking to ourselves’. We

can say with Thomas Mann’s words: if I were a conductor, I would conduct

like Walter. In listening to Toscanini, however, supernatural forces play

with us – such forces with which one cannot argue, that are irrevocable.

(How did Beethoven acknowledge it? ‘Above me is the starry sky, inside

me is the moral law! Kant!!!’ Diary, 1820.) His art illuminates the specific

aspect of Beethoven’s greatness that is not measurable with ‘human’ measurements

– the ‘immeasurable Beethoven’ that Berlioz also saw. Still, the humanism

of art can be found in this passionate love of truth. If Wagner called

the Beethovenian creation the ‘good person’s melody’, then we could say

that Toscanini makes the ‘true person’s melody’.

Let us add to this that later,

with the same inspiration, he brings to light the other secret of the Sostenuto,

which is that the ‘signature’ theme of the movement is found deeply rooted

in the Vivace organism (cf. Fig. 24).

Just a few more remarks.

The heightening that follows in the wake of the second theme is felt not

only in the quickening tempo of bar 29. Toscanini recognizes the acoustic

counterpole of the approaching storm in the pianissimo color that

replaces the piano that has been present until now. His violins

sing in a penetrating pianissimo, as if they wanted to tell intimate ‘stories’

12).

Toscanini believes that the piano, forte, etc. markings do not primarily

designate volume, but rather character

13).

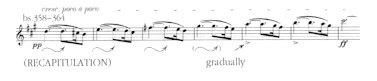

Then the melodic accents slide according to schedule at the crescendo marking

from the odd quarters to the even ones:

to which the accompaniment

gives the initiative.

In the unison sound of the

more than fifty times repeated ‘e’ of bars 57-63, every sound is weighed.

(It appears that this ‘e’ sound – this vox-repercussa 14)

– will have frequently returning symbolic meaning over the course of the

performance; see Fig. 107.) The repetitions tuned to the e at the

beginning of bar 59 suddenly stop with an accent as if they had hit an

invisible wall. The flute gives a delayed answer to the softened sound

of the violin on bar 60 (‘tired’ echo-sound). The embryonic main theme

is being born at this standstill 15). At

the turning point of bar 61, it is barely breathing, however a measure

later, the sixteenth up-beat of the flute sparkles expressively, and finally,

at the third attempt, the Vivace bursts open 16).

***********************

Most performers look for

the driving force of the main theme in the outstanding motoric pulsations

of the melody (as the concert programs call it: the twittering pulsations).

For Toscanini this idea meant something completely different. In his view,

the structure of the entire movement is reflected in the main theme, like

the whole ocean in a drop of water. That this is not a poetic exaggeration

is tangibly verifiable both inductively and deductively. Some of the components

of the theme possess certain characteristics and basic elements which affect

the further development of the movement; moreover they provide us with

a dramaturgical clue. The movement had to develop exactly according

to the pattern of the score, because the main theme carried the germ of

the movement’s development from its moment of inception. The reverse is

also true, however. The various connecting parts of the piece are built

up exclusively from each of the elements of the main theme. From the character

of these details, the meaning of the basic elements can be followed in

reverse. The scheme of the development and the coda, for instance,

is not even approachable without a knowledge of the elemental idea hidden

in the motions of the main theme.

Let us set out from the opening

bar (bar 67). Whenever this 3-note motive crops up in the course of the

movement, Beethoven uses it for the question-answer game between the instruments

– for the echo effect. He places the resonance in the ‘space’ (such as,

for instance from bar 142; at the beginning of the coda these echo and

space effects appear more noticeably – bars 393–400).

The second element of the

theme was not made from such a mold (bars 69–70). This thought drives

a sort of feverish activity – a desire for action, that is now being expressed

in the rhythm as well. The galloping ta-ti ta-ti basic rhythm is

unexpectedly stopped by an intruding ti-ta opposing rhythm. This

rhythmical conflict provides in itself an explanation for why we meet with

this motive precisely at the most tense points of the movement (e.

g. from bar 119).

The two basic elements of

the main theme do not just create opposition, but also create unity. Toscanini

unifies the opposing elements according to the laws of the dialectics of

language, hence the volubility of the interpretation. He arranges the material

into sentences, in the strictest sense of the word, and within the

structure of the sentence he clearly makes a difference between the roles

of ‘nouns, verbs, adjectives and conjunctions’. Let us just think of a

simple sentence, such as ‘the farmer plows’. It consists of two elements

– a noun and a verb. The word ‘farmer’ calls a picture to mind –

a picture that we unintentionally visualize in space. The other, the verb,

expresses an action, therefore its real dimension is time.

Do the above-mentioned musical

elements not tie together in a similar intimacy, however? That is the technique

with which Toscanini ‘places and displays’ the first two bars of the main

theme – this is painting in its entirety. The ‘vocalized’ notes between

the 1st and 5th eighths of the melodically revealing

opening bars are pictures. Toscanini strives for color-effects – the initial

notes open towards space, or as I would rather say: he makes the flute

sing into space. As we mentioned previously, even Beethoven himself places

this motive all through the exterior space during the course of the movement.

Therefore the accent rests

on the visual image and not on the action. The acting function of the verb

is fulfilled by the second motive (which is revealed in the tempo of the

performance). The polarized ta-ti ta-ti ti-ta rhythm shows that

this is the dynamic element of the main theme, which wants to ‘change’

at any cost. Moreover, as we have seen, it carries within itself the possibilities

of conflict. In the score, it is also noticeable that the accompanying

voices which have so far been restful, are now suddenly liberated

into elements of motion (the held notes of bars 1–2 and 5–6 and their resting

voices are being changed in bars 3–4 and 7–8 by the elements of motion: cf. clarinet, bassoon and horn).

Let us try to follow the

happenings of the performance with motions. We react unintentionally to

the first and second bars with upwards arching, opening motions, while

the third and fourth bars urge us towards downward strikes.

In the following, Beethoven

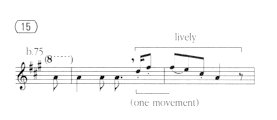

condenses the 4+4 bar structure systematically to a 3+3, 2+2, then 1+1,

and finally half+half bar structure. Toscanini consequently stays with

the earlier principle: he always couples a dynamic element with a static

element, keeping the fantasy of the listener active. It is in this that

he differs from the traditional interpretations. We usually hear the continuation

of the main theme as such: the f# -e-c# -a motive answers the sounds

of the a-d-f# of bar 75. In Toscanini’s performance manner, the

basic note (a), which is repeated four times, gains a static

character

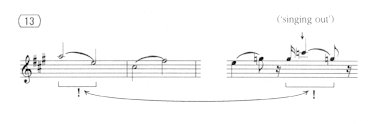

due to the repetition and divides the notes following it sharply from it.

Through the attachment of the d-f# -f# turn to the consequent, however,

there appears a joyful liveliness and teasing character in the melody.

What is even more interesting

is that this constructive line is not even broken after bar 80: Toscanini

explodes the forte-dynamics with sudden force (subito technique),

and thus the statically-stiffening E-major ‘column’ can only fulfill the

part of a noun (bar 82).

In the fortissimo

form of the main theme, Toscanini now connects larger units (he precisely

draws the 4+4 bar borderline by cutting the b-motif-ending note

in the 92nd bar) and differentiates between a half-cadence and

an authentic cadence. The authentic cadence (bars 95–96) answers with the

energetic braking of the tempo to the more vigorous rhythm

of the half-cadence (bars 91–92), for which the analogous turn of the recapitulation

provides an example: the heavily rhythmic bars 284–285, where the leaden

weight of the brass and percussion ends the chase. The immediate task of

this broadening of the tempo is to make its point of support a pillar

of form for the steep heightening that follows out of it:

(We must note that the notes

of the melody are not joined as triplets in motivic unity, but rather according

to the style of the previous sketch, and as we see, every repetition of

the motive climbs higher on the dynamic ladder.)

The dynamic structure of

bars 89–96 can be traced back almost naturally to the laws of attraction

as described in connection with the themes of Haydn:

For Toscanini, the score

is a dramatic scene. The events that closely follow upon each other obey

not the rules of form, but the particular laws of dramaturgy. (In the exposition

of the movement, for instance, we cannot even find a trace of the conventional

main theme-secondary theme-ending theme order.) The earlier compression

(exposition: bars 105–108) was accompanied by a violent agitato and acceleration,

but this time it does not lead to a stop (as in bar 88), but rather ends

in a crisis.

Toscanini dramatizes the

course of the conflict with his nearly sensational tools. It was not for

nothing that he was a theater conductor – he knows the psychology of excitement

and the function of the stage: the crisis signifies the medium through

which the development is made possible. In the middle of bar 110, which

according to the score is still fortissimo, he hits upon the source of

the crisis in the alarming stroke of the timpani. The suffocating excitement

of the next bars comes as a reaction to the alarming stroke. From here

stems the staggered rhythm, the square, choked galloping of the string

accompaniment (the panting caesura after the first quarter of every bar),

and last but not least, the rapid changes of the keys that are seemingly

‘unable to find their place’. (In the recapitulation, it proceeds in a

similar manner: the b-a-g# closing notes of bar 325 step aside in

fright with a subito diminuendo at the forceful drumming of the timpani.)

Conventional performances,

however, do not in the least reflect this commotion, although according

to the meaning of the frequent key changes, the staggered dynamics and

the abrupt motif, one could also conclude this. This difference of opinion

is even more flagrant at the climax. After an unsuccessful attempt (bar

115), bar 119 finally succeeds in heating it up. How could

it have happened, that from this melody, which in the opinion of formal

analyses is ‘insignificant material’, he liberates dance movements that

have elemental effects?

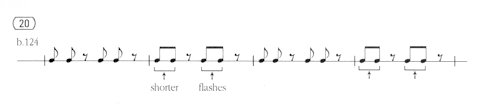

The counter-rhythm of bar

119 17) – the conflict fanning ta-ti

ta-ti ti-ta rhythm – is interpreted by most conductors as a resolution:

It is not so with Toscanini:

he sharply accents both notes of the ti-ta counter-rhythm

at the end of the motive 18). Thus the polarized

tension becomes active and liberates the elemental energies that are latent

in the rhythm:

For this reason, the above-mentioned

part is neither the supplement nor the epilogue of the main theme – that

is, it does not fulfill the task of rounding-off the form, as we are usually

accustomed to – but rather crowns, or brings the theme to its peak.

(In bars 112–118, Beethoven placed the ‘ta-ti’ galloping rhythm in the

forefront, so that he can realize this burst of activity with the ‘ti-ta’

counter-rhythm.) Moreover, the tension quickly becomes charged,

which shows itself in that the counter-rhythm pushes out every other element

and becomes independent (from bar 124 onwards it repeats 8 times):

Under Toscanini’s baton,

this music is indeed lightning (he makes the rhythmic patterns in the 2nd

and 4th bars flash more quickly). Nothing characterizes Toscanini’s

way of thinking better than the fact that bar 128 starts from this condensed

rhythmic tension, and not from that external fact, that in bar 130, he

glimpses a ‘new theme’ (certain guides believe it to be the secondary theme).

The immense blocks of chords at the climax crash down upon the sforzando,

which is resolved by the sigh ‘of relief’ of the woodwinds.

Toscanini sets this ‘solution’

in the mid-point of the construction of the exposition. Let us stay

at this point for a while. The post-romantic performance style only attributes

direct effectiveness to the ‘active’ actions. The performer unceasingly

strives to go somewhere – even in moments of calm and resolution, his facial

features distort in spasms of ‘active’ enjoyment, and he therefore cannot

recognize the finest fruits of his exertion – the value of those short

moments and the lawful joy that accompanies the quenching of the tension.

A romantically inclined artist wants to actively impress, seduce and thaw,

even with the resolution. Toscanini wants to redeem with the resolution:

he wishes to free from the weight of the tension, to unlock the shackles

of the spasm, and to soften and put out the fire of anguish. He does not

accomplish this with active deeds, but rather the opposite – with inactivity,

loosening, relaxation of the muscles and an end to the gripping. That is,

he does this with some sort of negative force, that nevertheless, stronger

than any activity, reaches the deepest roots of our physical and spiritual

existence, because it effects our familiar innermost being as the untamed,

natural reflex of existence. I confess that on my part, never has any type

of performance created so much joy as Toscanini’s ‘resolutions’.

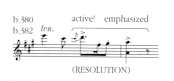

This is the significance

of the easing sigh and dolce that accompany the ‘e’ solution of b.130 19).

Afterwards, the released melody signals only a weak recovery (Toscanini

did not preserve anything from the sharp rhythms or pulsations of the main

theme, which he gradually softens into an almost ‘ta-titi’ throbbing).

This fluttering turn is primarily produced by the joy felt concerning the

solution:

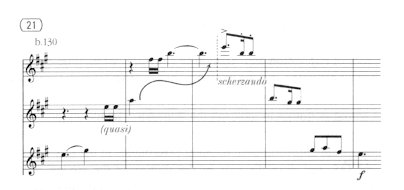

Only the scherzando of bars

132–133 answers somewhat more rhythmically, no doubt because it can return

to the ‘e’ (bars 134 forte). That Beethoven did not intend this to be a

secondary theme (at most a transition), is evident because he opens the

motive unaccented, in the middle of the bar. This picture is only broken

apart by the bold change of keys in bar 136 (E major to C major). The theme

returns with the stress of the bar, takes a firm stand, straightens itself

vigorously, and announces the greatest event of the exposition.

While we are on this subject,

let me add a personal anecdote. For a long time, I believed the weaving

of the motive in the opening movement of the Ninth Symphony to have a loose,

fantasy-like form – the pathless line of the melody sometimes popping up,

sometimes diminishing in fog and sometimes waving up and down as if in

a vision. Later when I became acquainted with Toscanini’s interpretation,

what had seemed to be an unfathomable tangle revealed itself with such

a concentration of creative logic that, with a sudden force, it provided

me with the key of the form’s construction. Toscanini puts the two choral-bars

– their sensuous, rainbow-colored string resonances – that appear in the

middle of the exposition in front of us with such complete beauty and harmony,

that, acting like a watershed, they cut the exposition into two

parts. Everything that previously was fight, struggle and strain

becomes fulfilled after these two bars.

Such a watershed divides

the exposition of the Seventh Symphony into two as well (bar 142).

It is a watershed not only between two worlds, but also between two fundamentally

opposite modes of perception. What has happened so far was

‘expression’, which took place because we wanted it, and the communicative

desire was within us, tensing in our muscles. What is revealed here

is ‘impressions’ – the magic of sound captures us from the outside,

and the floating sensation elevates us above ourselves. As if they had

changed the instruments of the orchestra, thus do the sounds begin to vibrate

and shudder. The glory of the colors – the ‘beautiful harmony’, which conventional

artistry places on a pedestal in a self-centered way, is only a tool in

the hands of Toscanini – a tool of expression and creation of structure.

When time comes for him to show the power of his baton, we are forced to

believe that ‘miracles’ are possible.

The pianissimo, like a light

maelstrom, appears above our heads (bar 142), and an excitement of spring

perfumes trembles in the tremolos. The technique that creates this magic

is built on the fairylike vibration and space-effect of the 2nd

and 4th bars. Toscanini glimpses the impressionistic painting

possibilities in the instrumental answers of bars 143 and 145, and, with

the help of the shifting of the violins, holds back the intonation of these

two bars like an ethereal echo (bars 143, 145). He makes us feel

with sensual excitement that this light floating, and this sensuous magic

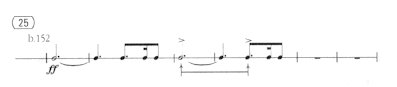

are indeed the forerunners of the fulfilling explosions in bar 152 20).

We can already observe that

on the peak before the watershed (bars 119–124), the ‘active elements’

of the main theme claimed leadership, while after the watershed

(bars 142–151), Beethoven allows those components of the main theme to

prevail in the impressionistic picture, which represent the picturesque

21)

element:

In summary: before the watershed,

the crisis is triggered from the dynamics of the inner emotions, while

beyond the watershed, the external beautiful harmony dominates and

leads to the culmination.

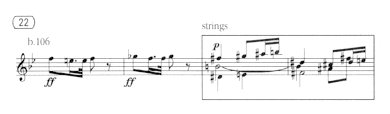

Toscanini realizes the culmination

of form and content of the exposition with unparalleled perspicacity.

In conventional performances, the motif generally goes unnoticed, because

the conductor places the rhythmic explosions into the focus of the heightening

(bar 152), and the motif itself is placed in the shadows. If we regard

the rhythmic explosions as mere reflectors, whose function is to lighten

the culmination itself, however, then we immediately realize that

this motive is none other than the opening theme of the symphony:

the emotionally enlarged version of the signature theme.

The material of the slow

and fast parts of the movement are thus incorporated into one arch by the

two motifs 22) (and so the dynamic

drawing of the signature-theme will have new light shed on it). But how

does this reflector work?

The blinding light intensity

is fed by the polar energy that is created between the inner tension of

the above accents (‘inner crescendo’). The same accent relations are taking

care of the fortissimo’s sudden interruption. In other words, Toscanini

energetically accents the last member of the rhythmic pattern, then

suddenly interrupts the process. Thus the explosion creates a ‘vacuum’

and, through the cracks, pushes the motive of fulfillment with unstoppable

force. Toscanini again was faithful to the score, since the rhythmic motive

should have been finished in such a manner:

Beethoven, however, tears

off the ending note and leaves only this from the formula 23):

What comes after this – the

dual-theme, rhythmicized with heroic freshness (a canon from bar 164) –

already confirms the safety and the final arrival. The performance accordingly

strives for maximum clarity of the material 24).

As we mentioned, Toscanini

builds up the exposition from the two opposite (both in material and tone)

components of the form. While the ti-ta counter-rhythm, which is

repeated 8-times, determines the boundaries of the end of the first part,

much like an ostinato, the ta-ti base-rhythm at the end of the second

part, which is also repeated 8-times, attains exclusive, absolute domination:

Toscanini outlines all this

even more radically with the shortening of the ‘iambs’ (as we said: with

flashes), or rather by the expansion and rhythmical overstraining of the

‘trochees’. (The protracted fourths of bars 171–178 snap away in sharp

staccato notes; the last eighth, at the end of bar 174, receives a murderous

accent.) With this procedure, he makes us aware of the fact that the overall

structure of the exposition also follows the construction of the main

theme:

***********************

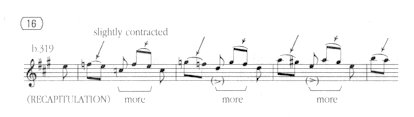

It would almost require a

separate chapter for us to discuss the dramatization of the recapitulation’s

main theme, which here first appears as fortissimo, and only afterwards

as piano (bars 278 and 301). The currents that work in the intonation in

all cases give evidence of a consciousness of performance: the maestro

stresses just those elements that cause the two parts – the fortissimo

and the pianissimo blocks – to functionally complete each other. His fortissimo

motive points forward passionately, thus leading Toscanini now to

stretch out towards new effects – ones that have not yet been applied in

the exposition. He ‘hurls down’ the motive endings in the heat of passion:

Whereas from bar 310, he

reverses the motive’s dynamic ‘cape’ 25):

As we see, he also adds to

the effect with echo-interactions (the bassoon and oboe reply to the clarinet

with echoes in bars 315 and 317).

If we wished to measure the

volume relations on the basis of the ‘density’ of dynamics, then the fortissimo

block of bars 278–299 would certainly determine the location of the center

of gravity of the movement. (With Toscanini, this is genuine ‘heavy cavalry’,

or at least a precursor to the ride of the Valkyrie.) It is exactly this

that gives exceptional meaning to the metamorphosis (after bar 300),

for there is always something moving when we succeed in spying upon one

normally known for his energetic, unapproachable greatness, in one of his

gentle, intimate moments. The suddenly emotional moods of Beethoven, Bartók

and Toscanini strike deeper than those of Petrarch, Werther or Wagner,

because they always firmly opposed sensual temptation. If the fortissimo-block

was the center of gravity of the movement, then the metamorphosis after

bar 300 leads to the subtlest display of the performance. A delicate

smile flutters along bars 309 to 318. Let us think of the airily breakable

(the ‘coming up with gentle caresses’) dolce sound and the murmuring ‘endearing

turns’ of the instruments that receive their musical shape in the previously

mentioned softening and breath-like echoes. Let us not forget for a moment,

however, that only the polar organization of the material justifies

Toscanini in this sensuous melting.

The dolce intonation is already

present from bar 301, and the theme-heads of bars 301–302–303 become a

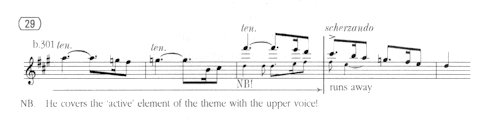

little dreamy, later escaping into a delicate scherzando:

This time, Beethoven himself

makes the active elements of the theme disappear (he covers them up

with the upper voice), and also creates the upper voice from the material

of the first bar.

What I would like to speak

about at this time is one single chord. Between the already analyzed two

parts (the forward-moving fortissimo and the withdrawing piano blocks),

at the sudden stop – like at the meeting point of two lines of force –

there stands a quiet chord: a frozen, unmoving wind-chord. I still cannot

find an explanation for the shock created by this dead chord (bar 300).

The chord expresses with staggering suggestivity that we have stepped into

a ‘no-man’s land’ between two worlds.

***********************

The formation of the development

into an action is no small dramatic task in the organization of the material.

Here as well we can find that bridge, that makes the meaning of the world

suddenly change after we cross it. This metamorphosis, however (in comparison

to the exposition) happens in the reverse direction. If allowed, I would

call this turning point the ‘rainbow bridge’, which not only indicates

the center of the middle part of the movement, but the most daring distance

from the A major tonality of the work: Db

major and F major

together with the A major create an augmented third relationship. The prismatic

diffraction of their direct linking becomes the most unexpected harmonic

happening of the movement. It turns this rainbow game into an intangible

and delusive reflex of distance, that gives a necessary new turn to the

happenings.

If we now look right and

left from the central point, not only do the symmetries of the development

take shape in front of us, but the concept of opposition of content

hidden in the symmetries is revealed (and once again hits us with the force

of discovery).

In both the first and the

second halves of the development, Toscanini puts the shrill screaming of

the winds in the center of his construction (the ‘basic rhythm’ stripped

down to a formula). While the – in melodical sense – stiff clamor

of bars 205–206, 211–212 and 217–219 describes above all painting, color,

fresco, and molten sound-pictures, the galloping vision of bars 254–267

grabs us with the force of motion, action, doings and dynamics. In other

words, the first half of the development is occupied by static elements

(repetition of sound). The second half, on the contrary, releases active

elements. Everything that occurs in the course of the development is in

the service of this dual structural plan.

First, let us ask how we

could prove the solidity, the static strength, and the capacity of an object.

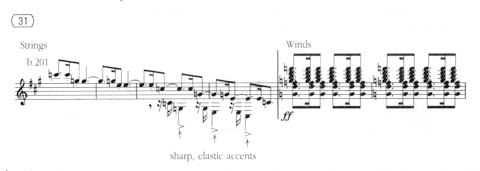

Without a doubt, we must load it with counterweights. Toscanini

indeed uses this ‘loading test’ on the thematic material of bars 201–219.

The ecstatic stiffness of the clamor of the winds is being counterbalanced

by the ‘crushing rocks’ of the strings and timpani. Thus, this transitionless

change from plunging to motionlessness happens almost against the force

of gravity, and like a natural reaction (almost a thermal reaction), heats

up the color of the winds to such a clamor.

I look back on these few

bars as one of my earliest experiences with Toscanini. After the dizzying

free fall with the elastic accents into the deep, the clamor of the wind

instruments follows with such abruptness (I would like to say, with a lightning-like

straightening of the listener’s back), that perhaps I am not going too

far in speaking of an ecstatic, rhythmic trance, inasmuch as the stiffness

signifies the extreme degree of unconsciousness, or the concentrated state

of hypnosis 26). This fanatical ostinato-ecstasy

is none other than the abstract and stiffened form, rhythmicized on one

note, of the formula of the movement’s and work’s basic motion.

What is perhaps an even more

exciting task than this is a comparison of bars 217–219 and 250–253, since

the technical solutions in both are based on alternating answers between

the strings and wind-instruments – but with what diametrically opposing

meaning of content!

In the first case, we stand

directly in front of the ‘rainbow-bridge’ that links the two sides of the

development (bars 217–219). Let us imagine the argumentative dialogue as

if the strings and the winds were to position themselves on duplicate stages.

Toscanini creates this effect by sharply cutting off the ending note of

the strings, without any reverberations, compelling the listener to pay

attention to ‘space’. Thus the answer of the winds can strike back now

from ‘beyond’. The score most effectively justifies Toscanini’s interpretation.

The spatial effect – the idea of ‘here’ and ‘beyond’ – ties together the

c#

of

the strings and the f of the winds, in the same manner as the rainbow

bridge also leads from c# to f, connecting this bank with

the other:

Suitably for the symmetrical

structural plan, we encounter the alternating answering once again in the

second half of the development. In contrast to the earlier acoustical

meaning of the string-wind reflexes, bars 250–253 drive the most mobile

desire for action. The wind instruments no longer echo the strings,

but on the contrary, they passionately stand out beyond the strings:

In the glittering game of

bars 222–235, perhaps because here we arrive at the middle point of the

development, a countercurrent flows between the wind and string parts.

Above, in the theme of the winds, the melody head becomes always

sharper in pattern and the closing notes become devoid of tension, while

below, the opening bars of the string voices are more loosely woven

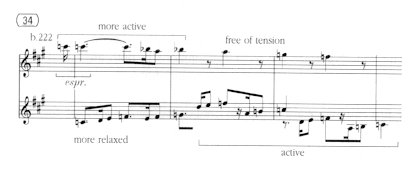

and the closing member becomes more active and more personal:

At the beginning of this

study we almost unintentionally exposed the symmetrical correlation between

bars 195–200 and 236–249 (cf. Fig. 6). Now we can at

most observe in surprise that all of the repetitions of notes in

bars 195–200, and all of the mobile voices of bars 236–249 fit into

the polarized plan with self-evident and natural logic:

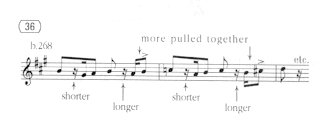

The forward-swinging of the

bars that lead to the recapitulation (from bar 268) is caused by the sharper

rhythm of the two notes at the end of the bar:

and the momentum of these

carries also the pulsation of bars 274–277 further ahead 27):

Finally, let us take a glance

at the coda. With the help of the maestro, here we arrive closest

to the genesis of the basic elements of the main theme. Perhaps it is not

necessary to prove that this time the steepest ascent of the movement has

to become reality and the power of the wild heightening can only be increased

if we arrive at it from a resting point. As a result of this,

the components of the theme create new relationships with each other. I

would characterize in short the form as thesis, antithesis and synthesis;

that is, the passive pictorial elements of the theme as thesis,

then the active, mobile elements of the theme as antithesis, and

finally, at the climax, the two together.

The exclusive building blocks

of the first part (391–400) are the three opening notes of the main theme.

The compositional technique here is based on the interplay of colors, full

of refraction of light and ‘distuning’. The harmonic connection, that in

the case of the above-mentioned rainbow bridge was a one-time surprise,

here becomes a law (major triads related to major thirds overlap each other:

A b

and C major, F and A major; in addition, A

b

major and C major have an augmented third relationship with the expected

dominant E). Toscanini’s palette of colors was perhaps only this airy,

and so translucent at bar 309. The melodic arches, the echoes and reflexes

step out of the impressionistic painting in such a manner that where

they came from is not even determinable. Each melodic arch advances towards

‘openness’ (the notes reveal themselves almost with the logic of the sordino

opening of a wind instrument) 28):

We will later return to the

role of this effect in form. From bar 393, the first violins always answer

the questions of the second violins in a gentle echo. Toscanini ‘snatches’

the pianissimos at the end of bars 397 and 400 (bitten-off Puck-like

chuckles) with a refined irony. Thus these barely audible, hidden rejoicings

become the point of the melody…

Finally, the highest lightness:

the arches of bars 398–400 that slip away into sparkles, or rather, their

‘fragrances’, which dissolve the melody into pure colors, the harmony in

refraction of air, and the line with volatile optical apparition. All of

this Toscanini, with his spiritual outlook, renders as a unique and unrepeatable

‘visual’ event, the deeper meaning of which is eventually given by the

chromatics of the bass ostinato, peeping in the darkness (from bar 401).

The dramatic seed of the

active

second member of the coda is the obstinate opposition of the two parts.

The initiative is first taken by the serpentine bass, but from bar 415,

a tangible change steps in, so that eventually, the upper voices of bar

423 break into a triumphal exultation. The course of the struggle, from

the dark beginning to the achievement of victory, is confined by the balance

of power between the opposing voices. The technical realization of this

intensification would be impossible without the immediate, or rather the

most immediate, interaction of the violins and basses. It is only in the

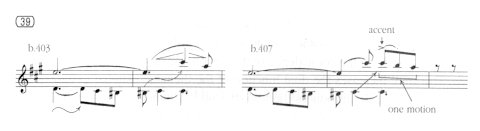

frame of this ‘dual theme’ that there are grounds for the soaring of the

violin crescendo in bar 404 as well as for the first motion of breaking

through which occurs four bars later 29):

The crescendo, or let us

call it the charging of the form’s battery, is also fostered by the outermost

voices: at the positive pole, with the ‘trochee’ base rhythm of the violins,

and in the negative bass-pole, with the conflict-stirring ‘iambic’ counter-rhythm.

The outcome of the battle, however, is only decided by the last one and

a half bars. At the end of bar 421, the timpani ‘explodes’ through the

orchestra (we encounter a similar impulsive effect perhaps only in Klemperer’s

recordings) and frees the fanfare-motive to the surface. How characteristic

of Toscanini that he is able to increase even the effectiveness of these

fortissimo chordal blocks with the help of the more throbbing, more sharply

edged rhythms of the even bars (bars 424 and 426).

Here already, the interjections

take the lead. The relationship between the short caesura and accent as

shown below becomes more aggravated in the stamping of bars 433–437:

so that the third member

of the coda, and at the same time its synthesis, can burst out from

this. In the first member (in the pictorially composed bars 393–400) the

exclusive thematic material was the motif, that we considered as the ‘subject’

of the main theme. Contrastingly, the second member (the tense bass-ostinato

of bars 401–420) is driven by the motif and rhythm that was the mover of

the ‘predicate’ of the main theme:

(To all this, Toscanini’s

sound-fantasy adds the most crucial characteristic: both motifs reach the

middle of the bar with a crescendo, but while the first case goes from

a closed intonation towards an open one – that is, it was an expansion

–, the bass-motif stretches the muscles of the structure, as if it ‘compressed’

the intonation).

After the two analyzed parts

– the thesis and the antithesis – bar 442 achieves synthesis on the account

of the ‘subject-predicate’ relationship. With the raw confrontation of

the two elements, in the coincidence of the ‘visibly sensuous’ and the

‘wilfully active’ worlds, Toscanini increases the dual function of the

thematic material to almost super-human proportions. He introduces the

melodic

and rhythmic elements in the middle of the brawl; on the one side

with a high-crying horn-wind call, and on the other side with the violently

interrupting timpani:

The inclination of the ‘singing’

element to expand and the moving force of the ‘active’ element increase

towards ecstasy. While the melody stridently overpowers the wilful rhythm,

the rhythm endeavors to rebuff the overflowing colors of the melody.

The capability to summarize

the basic elements as well as the capability for such a degree of concentration

of the material out of which experiences are made – the truly Michelangelo-like

features in Toscanini’s art – led Aladár Tóth 30)

to think of these ‘marble blocks’ when he saluted him as the successor

of the great renaissance Italians.

(The grim static character

of the two closing bars not only puts an end to the movement, but also

gives an initiative for the change to the suffering minor key of the Allegretto.)

Was there another among the

orchestral artists of this century who could have felt the laws of musical

dialectics so unerringly, with an almost impersonal security in his cells

and nerves? Toscanini’s recording of the Missa Solemnis made me

suddenly aware that this artist really cannot say two ‘credos’ or ‘pacems’

one after another without the first reflecting a tense motion of

skepticism, and the second reflecting unshakeable belief and affirmation.

Perhaps it is this simultaneous

negation and affirmation that opens his way to the rediscovery of Beethoven.

2) Usually

a peak note or a tense ‘subdominant degree’ (the 4th or 6th degrees of

the scale).

3) This

is even more palpably evident in the 1936 recording.

4) Fundamentally,

bars 3–4 follow the course of the first two, with the difference that (as

a result of the previously mentioned principle) the oboe’s melody of the

4th bar becomes more sensitive, its fourths being warmed by gentle tenutos.

5) Harmonically,

this is also a breakwater: note the appearance of the tension in the subdominant.

Toscanini unmistakable warns us through the elongation of the two eighths

at the end of bar 6 that a climax will follow.

6) Increasingly

lengthened quarter notes.

7) “Ew’ges

Ur-Vergessen” (Wagner: Tristan and Isolde, Act III)

8) That

is, he increases the strength and value of the experience by allowing the

fulfillment to last a short time only. Toscanini makes clear with unrivalled

security that something ‘has begun’ at the end of bar 9. (cf. Fig. 10).

The threefold scalar steps of bars 10–12–14 represent three degrees. The

playful excitement of bar 10 is expressed through its light staccatos,

on every quarter accent, that are elongated by tiny joyful hiccups. A certain

amount of tension is mixed into bar 12 by the repeated c# exposed in the

beginning of the measure. Toscanini already brings larger units together:

Finally, the stretched

third degree reverses the dynamics, and whether one likes it or not, drags

the listener by the hair along with it:

From bar 15 onwards, the

monumental construction is also manifested in the clear articulation of

the thematic scheme. The beginning and end of the 8-tone scale groups are

almost palpably tangible (and with this the construction also prepares

for the rhythm of the second theme – cf. bars 24 and 26–28.):

particularly from bar

18, since the earlier bars are still under the dynamic sway of the volcanic

eruption.

9) If

the main theme’s pulsation lives in common knowledge as having a ‘twittering’

rhythm, then here, with a similar play on words, one could say:

10)

Beethoven himself makes use of this relation in bars 32–34 in order to

join the two themes together.

11)

The aforementioned ‘punchline’ of the melody finds its place in the structure

by falling on an even measure. This is why the playful scale of

bar 22 was already so lithely active (Toscanini moves the two and four

quarter groups more animatedly). Let us add to this, that he gently lets

the two eighths at the end of the passive bars (23, 25) go, so that he

can start bars 24 and 26 with a tense tenuto.

12)

Thus a peculiar duality arises between the melody and the accompanying

ostinato.

13)

Toscanini happily mentioned that he received his first lesson with respect

to this from Verdi himself, who at the rehearsal for Otello drew

the attention of Toscanini, who was sitting in the cello section

to this: what is such a pianissimo worth that cannot be heard? The pianissimo

expresses character and not volume!

14)

In old music, this phrase did not only mark repeated notes, but also the

dominant of the key.

15)

The violin and flute change places with each other: the flute-signals go

to the beginning of the measure.

16)

Bars 42–52 only differ from the earlier interpretation of the theme, in

that Toscanini holds the melody together better. While the tense g#

of bar 54 and the even tenser b note intonate the melody (so that

the picture can burst open with the fp of the next measure), the

same melodic turn is treated as a passive element in bar 56.

17)

It is enough to quote the opening movement of the Eroica to illustrate

what a lively role the complementary rhythms play in Beethoven’s thought

processes:

cf. further with bars

201–206 from movement III of Seventh Symphony.

18)

This holds even truer for bars 331–339 of the recapitulation.

19)

It is impossible for me to refrain from adding an analogous example: The

unforgettable introductory bars of Toscanini’s recording of Missa Solemnis.

The secret of the effect here too lies in the resolution – in the liberation

from the weight of the tension – this is expressed in the low, satisfying

sigh of bar 6:

(Beethoven’s own notes

point to such a meaning, for we can read such remarks as ‘durchaus simpel’

and ‘les derniers soupirs’ in his sketch-book, at this and similar turns).

20)

The heightening in the exposition is somewhat more impatient than in the

recapitulation. The hastened accent-points of bars 358–360, as will soon

become clear, will reveal something of vital importance about the motive

itself and its inner dynamics:

21)

I adapted this terminology from the Bach-analyses of Albert Schweitzer.

22)

At the other ‘key-point’ of the exposition, in bars 126–127, a similar

motivic structure appears:

23)

In the recapitulation, this rhythm is even more forceful (bars 364–373).

24)

For instance the violin part of bars 166–167 – in accordance with the score

– does not use sforzandos, so as to make room for the bass theme. The resolutions

of the exposition and the recapitulation are slightly different from each

other. The following motive

in the case of the recapitulation,

closes the theme with resolute motion, signaling that the work has come

to a resolution. In the exposition that same motive is less assertive,

and rather permits the imitating bass to assert itself, since the development

still lies before us.

25)

Unsurpassed sweetness emanates from the separate beginnings of the two

staccato notes at the end of bars 309 and 311 (as it also does from the

piano-pianissimo of the oboe melody in bar 317).

26)

Cf. Ortega: Sketches on Love (Love, ecstasy, hypnosis).

27)

That is to say, Toscanini carries the metrical tension forward to the middle

of the bar. He unexpectedly slows the tempo of bar 277, and seizes the

middle of the bar, as an up-beat of the main theme, with an even more powerful

motion. The same thing also occurred in the analogous place – in the middle

of bar 66.

28)

Only the very first motif (bar 393) sounds out in a more pronounced fashion.

29)

Here Beethoven specifies the first staccato and rest in this crescendo

part. This is why Toscanini adheres to the unshaded legatissimo of the

score in the violin parts of bars 401–402 and 405–406. If we have already

examined the c#-b-a turn of bar 400 and the c#-b-a

turn of bar 408 separately, let us mention that Toscanini, precisely with

the help of this c#-b-a rhyme, also illuminates the

existing relation between the contents of the two.

30)

Musicologist, famous Hungarian musical critic (1898-1968), [transl.]

Contents

|