|

Temporal arts, rhythm and periodicity

While noting the common root of the words "rhythm" and "number" (rythmos and arythmos) and speaking about the nature of rhythm, the common basic element of all temporal arts and especially music and poetry, M. Ghyka defines rhythm as "...observed and recorded periodicity... It acts in the measure in which the same periodicity deforms the regular flow of time in us... Thus every periodic phenomenon perceptible to our senses is singled out from the set of irregular phenomena... in order to act upon our senses by itself..." (Ghyka, 1987, p. 191). At the same time this definition points to some of the essential properties of our perceptive-cognitive apparatus: selectivity, the principle of economy, and the capacity to focus. While himself possessing a natural dual periodicity (the rhythm of heartbeat and of breathing), the listener of music or poetry experiences rhythm as a motor component (spatial movement) and he attempts to enter into resonance with it. At the same time, the principle of duality ("yes - no", "black - white", 0 - 1) also becomes very expressed. Within rhythm it occurs as an arrangement of durations and rests, especially through the arrangement of accentuated and non-accentuated parts. The principle of accentuation occurs with all periodic isochronic phenomena as a dynamic component. It is the manner in which we mentally substitute the meter corresponding to the equally spaced tac-tac sound of a pendulum with the tic-tac rhythm itself. On the level of rhythm, when translating the note durations to the language of numbers and symmetry, we get the "rhythmic code" of a musical piece (Chapter 2). We can study the arrangement of accents in a similar way. The patterns that are formed by the arrangement of accents within rhythmic groups are based on the principle of mirror symmetry (Meyer, 1986).

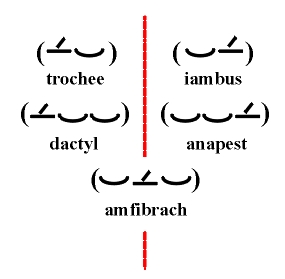

By assigning each sequence of non-accentuated elements a number equal to the length of the sequence, where a zero on the first or final position denotes an accent on that position, we can very precisely study the arrangement of accents within a musical (poetic or literary) piece, as well as its symmetric structure. For example, the sequence of numbers 01111... corresponds to trochee grouping (Fig. 9.4a), 11120... corresponds to iambic grouping (Fig. 9.4b), 01222... corresponds to dactylic grouping (Fig. 9.4c), 2222221… corresponds to anapestic grouping (Fig. 9.4d) and 12220... corresponds to amphibrach grouping (Fig. 9.4e).

(a) (b) (c) (d) (e)

In studying the "prosody of language," the alternation of accentuated and non-accentuated syllables in Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, V.A. Koptsik states that in the whole novel there are only about ten instances of deviation from the established rhythm based on the auditory pattern AbAbCCddEffEgg. In this manner on the rhythmic level Eugene Onegin represents a one-dimensional translation structure, a "rhythmic mono-crystal" (Shubnikov and Koptsik, 1972, p. 300).

|