|

TONAL

ORGANIZATION

Tonality and harmonic

organization are questions that should be approached from two areas: that

of "12-tone music" and that of its diametric opposite - "classical

harmony". 12-tone music confronts us with a musical ideal that seeks

to neutralize classical major-minor relationships, and be "intertonal"

1);

consequently its harmonic building blocks will be tonally neutral or tonally

indifferent equidistant chords (chords of equal pitch division)

and their combinations, namely the circle of fifths or fourths:

| and the equidistant

divisions of the octave: |

c

|

-g

|

-d

|

a

|

-e

|

-b

|

-f#

|

-c#

|

-g#

|

-d#

|

-a#

|

-e#

|

-b#

|

| the augmented

fourth chord |

X

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

| the augmented

triad |

X

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

| the diminished

seventh chord |

X

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

-

|

X

|

| the whole-tone

scale |

X

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

X

|

-

|

X

|

| the chromatic

scale |

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

Let us examine

more closely in what manner the vocabulary of equidistant chords forms

itself into the organic tonal system, which provides the harmonic

unity of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, and of Bartók's

music in general.

In the list given

above, the only item which embraces the whole chromatic scale is the circle

of fifths or fourths. One of the nearest natural harmonics, the perfect

fifth, together with its inversion, the perfect fourth, is treated

by Bartók - perhaps due to the influence of folk music - as the

"queen" of intervals. Following these considerations, and the lessons to

be drawn from analysis, the foundation of the present theory will be the

"tonal compass rose" - the circle of fifths or fourths.

The augmented

fourth (=diminished fifth) provides the constituents of the diminished

seventh chord, while the whole-tone scale - lacking as it does possibilities

for combination 2) - proves to be impotent

as a form-creating element; the main components of a system based upon

the circle of fifths or fourths will therefore be primarily the augmented

triad, and the diminished seventh chord. Let us see how!

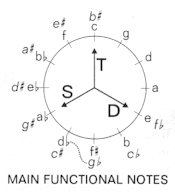

A precondition

of any system of tonality is a central point in relation to which others

are dependent or subordinate. In the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion,

the tonal system's central point c offers itself for the role of

the

"ruling" tonic note. If we set beside it "ministers" - on the right side

a note with positive tension, on the left side a note with negative tension

- then we have already simplified the question of the governement of the

circle of fifths. Suitable for just this purpose is the equidistant

tripartite division - ab-c-e

- of the circle of fifths, the

only question being what function we should apportion to the notes e

and ab. If we look at the practice of

European music, then e, the major third above the tonic, may with

impunity be considered a dominant, and similarly ab, the major

third below the tonic, a subdominant. Even in classical harmony we find

these are lent a similar significance.

3)

Now we shall examine

how the influence of the main functional notes - the tonic c,

the dominant e, and the subdominant ab

is

distributed. If we proportionately divide the 12 tones of the chromatic

scale between the 3 main functional notes, then each function acquires

4 "poles". The only arrangement of these poles that serves our ends,

is to quarter by equidistant division

the circle of fifths - thereby

matching the "intertonal" musical ideal of 12-tone music - in which case

we arrive at diminished seventh chords.

The following

can therefore be affixed to one another:

the diminished

seventh chord c-eb-f#-a

to

the main note tonic c;

the diminished

seventh chord e-g-bb-c#

to the main note dominant e;

the diminished

seventh chord ab-b-d-f

to the main note subdominant ab;

this especially when

we consider that the tonic character of c and a

(degrees

I and VI), the dominant character of g and e (degrees

V and III) and the subdominant character of f and

d

(degrees IV and II) agree with the principles of classical harmony.

On the other hand we have satisfied the requirements of 12-tone music by

each of the above listed "tonally" joined notes c-a, g-e,

f-d,

being neutralized by its "counterpole" - slicing diagonally the

circle of fifths - for example c is neutralized by f#.

This same result

can be arrived at based upon another theoretical consideration as well.

Taking note of the fifth-fourth attraction that binds the tonic to the

dominant (V-I), the dominant to the subdominant (secondary dominant), and

the subdominant to the tonic (I-IV), thus regarding Bartók's 12-tone

musical functions based upon the circle of fifths or fourths, we see the

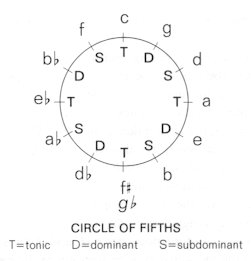

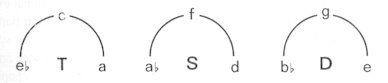

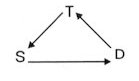

following system:

If c is

therefore regarded as the tonic, f (degree IV) as the subdominant

and g (degree V) as the dominant, then a (as relative to

the tonic) will have a tonic significance, d (as relative to the

subdominant) a subdominant significance, and e (as relative to the

dominant) a dominant significance. The circle of fifths segment f-c-g-d-a-e

is, therefore, matched by the set of functions S-T-D-S-T-D. In this relationship

a certain regularity is to be observed, as the S-T-D periodically recurs.

In essence the above diagram does no more than extend this S-T-D attraction

to the whole circle of fifths!

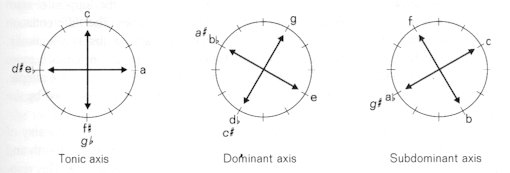

The clearly defined

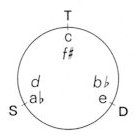

separate levels of the tonic, dominant and subdominant "axes" (to

coin a name, lacking terminology) remain either practically intact,

or are interrupted by an answer at the fifth during their participation

in the overall formal structure.

Within

each axis, viewed as a unified harmonic plane, the tonal tension produced

may be of two kinds:

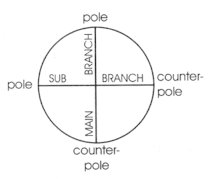

1. Tension

between the opposing pole and counterpole. By counterpole is meant

the note of the pole in the circle of fifths that at the same time splits

the octave in half, e.g. c and f#. This pole-counterpole

relationship should be regarded as one of the most fundamental formal principles

of the Sonata. A basic tenet of the axis system theory is that the

pole may be exchanged at any time for its counterpole without a change

of function. (A cadential harmonic progression E-A-D-G-C-F in Bartók's

system can, for example, be conceived as follows: E-A-Ab

-C#-C-F, in which the d and g are replaced by ab

and

c#.)

2. Tension

between the opposing main-branch and sub-branch. The "main-branches"

- in the diagram (Figure 3) - are the lines joining the counterpoles of

the main functional notes, that of the tonic axis being c-f#, that

of the dominant e-bb,

and of the subdominant ab-d.

(For this reason the terms "Bartók dominant" and "Bartók

subdominant" are used in this analysis to mean e or bb,

and

ab

or

d, respectively.) The

"sub-branches" intersect the main-branches at right angles, that of the

tonic axis being a-eb

, that of the dominant

g-c#,

and of the subdominant f-b. 4)

It is essential

that the individual axes be seen not as diminished sevenths, but as the

synthesis of two tritone relationships, i.e. as a scheme wherein the "opposite"

sides react to each other more sensitively than the "neighbouring" ones.

The differentiation between the main-branch and the sub-branch became necessary

not just systematically. We shall see how the "Bartók dominant and

subdominant" are given a much more emphatic role than the classically understood

dominant and subdominant. For example, in movement I a powerful appearance

of the tonic c is almost always preceded by the tonality of bb.

5)

A dominant-tonic

resolution, therefore, may be the following - in the tonality of c -

based on the possibilities inherent in the axis system: G-C, E-C, Bb-C,

the fourth and last being C#-C; that is to say, in the axis system

a dominant of C is also C#. This resolution is reserved by

Bartók for occasions when something unexpected takes place, such

as a change of scene. The explanation for this is that after C#,

cadentially we expect F#, whereupon the F# is surprisingly

exchanged for its counterpole, C, the expected C#-F# being

resolved instead by the "Bartók deceptive cadence",

the progression C#-C, (cf. Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, movement IV, bs.

73-74, 98-99, 113-114, 243-244).

The constituents

of the axis system, therefore, are:

| the "pole" itself |

- (without dimension) |

| pole + counterpole

= "branch" |

- (1 dimensional) |

| main-branch +

sub-branch = "axis" |

- (2 dimensional) |

| T + D + S axes

= "axis system" |

- (3 dimensional) |

Unquestionably,

the instrumental combination of the work, with the neutral sound of the

percussion, provided a very attractive opportunity to thoroughly put into

effect a tonal conception of this nature.

The minor third

intervals that lie between the poles of a particular axis can best be compared

to the relative major-minor relationship in the classical harmonic system.

Nonetheless, the concept of "tonic", "subdominant" or "dominant" axes does

not accord with the similarly named concepts in classical harmony. Thus

the dominant axis resolves onto the tonic not via a leading note, but upwards

via a dorian leap of a major second (often to be observed with the progression

bb-c),

or downwards via a phrygian leap of a minor second (db-c).

In contrast to the classical dominant-tonic relationship (i.e. T-S-D-T),

the axis system often follows the plagal succession subdominant-tonic (i.e.

T-D-S-T).

The extraordinary

tension of Bartók's tonal system is very much connected to the fact

that it arises as a struggle between two spheres of opposite attraction:

major-minor tonality (the tonality of diatonicism) and the axis system

(the tonality of chromaticism).

If we look back

at the history and development of harmonic thinking, then we are bound

to say that the birth of the axis system was a historical necessity,

signifying the logical continuation of the development of Western music

and to some extent its climax. At the beginning of harmonic thinking, a

tonic, subdominant or dominant significance was clearly ascribed only to

degrees I, IV and V of the scale. Classical harmony began to include primary

and secondary triads, degree I being replaced by the relative degree VI,

degree IV by the relative II, and degree V by the relative III. Romantic

harmony went even further, making extensive use of the upper relatives,

for example in the tonality of C:

| as tonic |

c-a-eb |

| as subdominant |

f-d-ab |

| as dominant |

g-e-bb. |

From here it is

but a short step to the system "closing up": the axis extends the employment

of relatives to the whole system, since f# is a relative common

to the tonics a and eb,

b

is a relative common to the subdominants d and ab,

and c# is a relative common to the dominants e and bb.

The functional principle remains unchanged by all this; it is simply that

the number of juxtaposed planes has increased and become more diverse -

thanks to the twelve tones. Bartók's harmonic system, therefore,

is not a resumption or a new departure, but a climax and a fulfilment

(indeed historically speaking, the axis theory has a certain retrospective

aspect for musical research). Here a distinction must be drawn between

Bartók's dodecaphony and Schönberg's "Zwölftonmusik".

Schönberg demolishes and annihilates tonality, while Bartók,

with heroic effort, amalgamates the principles of harmonic thinking into

what is so far the most exquisite and perfect synthesis, one which matches

the technical standards of the times.

Here we must also

touch upon the acoustic interpretation of the axis system. A proviso

of moving from the dominant to the tonic is that we move from a harmonic

to the fundamental. According to this, the dominant of c

will be not only g, but also e and bb; it was precisely

these that went to make up earlier the dominant axis main-branch.

And because the

| D-T relation

corresponds to the |

| T-S and |

| S-D relations, |

then e and

bb will

be the dominants of the tonic base note c,

c and f#

will be the tonics of the subdominant base note ab,

and ab

and

d

will be the subdominants of the dominant base note e:

If to this we

add the role played by the harmonic at the fifth, then from these relationships

the complete axis system can be demonstrated.

An undeniable

prerequisite of an "axis-like" organization of the tonal system was the

given nature of musical feeling in general, and the fact that Bartók's

ideas derived from the best traditions, not just regarding their theoretical

organization and execution, but - what is even more significant - their

meaning and content as well. At this point the revolutionary endeavours of Liszt

and Moussorgsky come to mind; the pieces by Liszt built from perfect

equidistance - unfortunately little known - and the "axis system"

experiments of Moussorgsky. Without exception, all of these, from the "Nuages

gris", "Unstern", "Preludio funebre", death music ("R.Wagner. Venezia")

and ghostly "Funeral gondolas" of Liszt (all late piano pieces) to the

Mad Scene from Boris Godunov (pure axis system), reflect the negative side

of life - dark, demonic and irrational experiences. These ideas, either

consciously or unconsciously, also find expression in Bartók, in

that for him, chromaticism (12-tone music, equidistance, the axis

system) is synonymous with a demonic and irrational world, while diatonicism

is associated with an optimistic and bright one - a subject returned to

and further demonstrated in the chapter entitled "Meaning".

To summarize,

therefore: the above tonal system of Bartók has been shown from

four different perspectives: 12-tone music (symmetrical divisions

of the system), classical harmony (functional relations), the historical

development of music, and acoustics. That in every case these result

in a congruity of means, shows that Bartók, when he created his

musical material, penetrated to the roots of music, to its most inherent

elements. Everything that was true he recognized as the truth, and out

of these truths he created a most exquisite unity. Before dealing further

with a demonstration of the axis system, we must turn our attention to

a number of matters concerning Bartók's use of proportion.

* * *

It is suggested

that the reader, before commencing any detailed dissection, should study

the extracts below on the basis of the present analysis: movement II

bs. 5-13 and 48-56, movement I bs. 61-68, 195-216, 232-247, 417-443.

1) Lendvai

here coins a new term, "hangnemközi". The Hungarian means literally

"between keys", translated here as intertonal (remark of the translator).

2) As

the combination of two whole-tone scales produces the chromatic scale.

3) E.g.

the first half of the development section of movement I falls under the

E dominant (161 -) and the second half under the G# subdominant (217 -).

A similar structure is also revealed by the second subjects of movements

I and III:

movement I from 84 is in E, from 95 in Ab

movement III from 44 is in E, from 74 in G#

Further good examples

are the sequence of tonalities in the Rondo in C major (C - E - Ab-

C) and movement I of the Concerto for Orchestra: Exposition in F (76),

Development in Db

(231) and A (313), Recapitulation in F (386). In Beethoven's sonatas

the dominant second subject often appears on the upper third of the

keynote (e.g. the C major Waldstein Sonata's second subject in E major),

and the subdominant slow movement on the lower third of the keynote (e.g.

the C minor Pathétique Sonata's Adagio in Ab).

The sequence of keys in Brahms' First Symphony is: movements I and IV in

C minor and major, movement II in E major, and movement III in Ab

major.

4) Cf.

movement I bs. 235 - 247: placed opposite the subdominant d - g# main-branch

(bs. 239 - 241) is the f - b sub-branch (bs. 244 - 247); bs. 417 - 443:

the first section instead uses the tonic eb-

a sub-branch (417 - 432), while the second section uses mainly the c -

f# main-branch; the outer sections of movement II are based upon

the subdominant axis b - f sub-branch, and the middle section on the d

- g# main-branch, etc.

5) The

bbb

chord, introduced later on.

NEXT

Contents

|