|

SICHER DEN KIEL (modal serialism)

The difference between ’tonal serialism’ and ’modal serialism’ lies in the fact that in the former the variety and diversity of the 24 major and minor chords are exhausted, while the latter exploits the possibilities of the 12 chromatic degrees. The ’exposition’ of Act I in Wagner’s Tristan brings into

focus the following sentence:

Our analysis has been centered around five moments: (1) "Auf jeder Stelle wo ich

steh ... " Where is Tristan standing? Above the maelstrom: in the gate

of hell, so to speak (bs. 1-4).

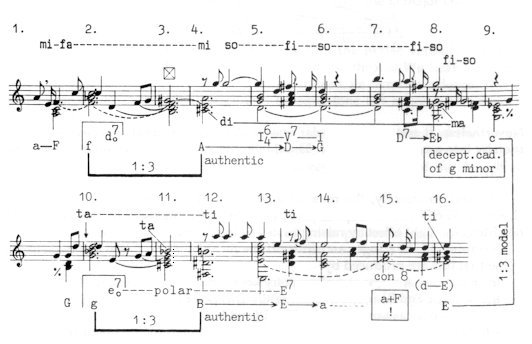

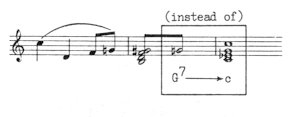

Let us consider these points one by one. (1) The MI-FA step has the pressing force of a steam boiler. Wagner begins the melody with A minor and its negative substitute chord: F major. The precipitous fall at the beginning of the Death motif was also effected by the motif bursting forth in the negative substitute chord, in place of the tonic. The ’balance’ tips over at the meeting point of the two worlds – in b. 3: the transition is marked by the two ’atonality points’ of our tonal system, RE and SI = D and G# (and FA-TI = F-B). In bars 2-3 it is already the C minor that we sense to be the tonic – which means that the third bar (dominant diminished seventh) should be continued like this: Fig. 220

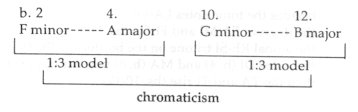

Nevertheless, it resolves in a polar way to A major (six accidentals away), entering thereby into a new sphere (b. 4). The C minor triad manifests itself openly as well in b. 9! (2) And conversely, the musical analogy of "Frauen höchster Ehr'" is the up-shooting FI-SO (the sweeping dash of notes F#-G in bs. 5-8). Wagner further heightens the light effect by raising bs. 5-7 to the dominant (G). Stripping all the fringes and frills off the melody, we find that the two surprises in the first line are produced by: the F minor—A major complementary

keys (’the colour of Tristan’s face changes’);

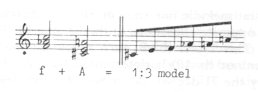

All this is extended by another two elements. The strophe sets out from A minor and its negative substitute chord, F major. This itself represents a big charge of tension. But Wagner does not stop here: he submits the two chords to another ’load test’ by converting A minor into A major (b. 4) and F major into F minor (b. 2). And with this he creates the possibility for a ’metamorphosis’, since the F minor + A major triads are complementary keys, annihilating each other (producing jointly a 1:3 model), as indicated in Fig. 221: Fig. 221

These chords act like litmus paper, which changes colour according to the acidity or alkalinity of solutions: the change of colour in b. 4 is eloquent proof of this. Thus, if we combine three principles: the substitute relationship:

A minor and F major

then the tonal structure of the theme can be clearly seen. In addition, the end of line 1 (C minor) and that of line 2 (E major) also reflects a complementary (annihilating) relationship. (See: Fig. 219 on p. 127) We note that also the F minor chord (b. 2) rhymes with the D major chord (bs. 5-7) in a polar way. (3) "Frauen höchster Ehr'": b. 8 gives away that the praise actually conceals ’contempt’. As if Tristan wanted to push Isolde off the throne! We hear a two-step negative cadence: G minor - in place of G major, indeed, its deceptive cadence! This is how the word "Ehr'" acquires a rough and brusque tone (Eb major = MA major), instead of reverence. It has repeatedly been pointed out that the deceptive cadence of the minor dominant is tantamount to MA major (Eb major), which is suggestive of sinister passions. And (typically of Wagner) even the deceptive cadence of the deceptive cadence is employed: C minor (b. 9). (4) The second line of the melody (from b. 10) repeats the first line a major second degree higher; this turn is known to represent the most powerful form of intensification: Tristan raises his voice! [NB: A major second rise = a change based on the modal dominant-tonic principle.] Bar 4 emerges as if the colour of the characters’ faces had all of a sudden changed. The litmus effect is elicited again: G minor (b. 10) and B major (b. 12) are complementary (annihilating) keys. The four analogous chords (bs. 2-4 and 10-12) encompass all twelve degrees of chromaticism: Fig. 222

The divergence of the first melodic line rests on the two-directional pull of the FA and FI. Similarly to the opposite attractions of the FA and FI, TA tends downward – while TI lures upward. This TA-TI (Bb-B) turn speaks for itself in bs. 11-12. The character of the E subminor (b. 10) is determined by the TA, and that of the E seventh chord (b. 13) by the TI degree. (Moreover, E subminor and E major are a polar distance apart: the monologue is propelled by an expansion of 6 accidentals.) The formula preparing the dénouement is one of the oddest achievements of Romantic music. The ’TI major’ chord (B-D#-F# in b. 12) borrows its peculiar quality from the MA and FI notes: D# (=Eb) gains a MA colouration, while the note F# a FI character. The chord couples the mortal ’human’ element (MA) with the uplifting ’spiritual’ element (FI). It is small wonder that the chord ushering the melody to its ’destination’ is the B major chord at issue. We have arrived at a point where Tristan’s famous sentence "Wie lenkt’ ich sicher den Kiel zu König Markes Land?" is uttered. (5) I can’t be far from the truth claiming that bs. 13-16 condense the gist of the Tristanian "Lebensgefühl" (’experience of being’). Wieland Wagner appropriately remarks that Tristan’s boat is headed towards the realm of the night – towards Nirvana – over the "Styx". The Oriental effect of the two final chords is due partly to the Phrygian mode (bs. 15-16), partly to the six-four tonality of b. 13, but first of all to b. 15, which simultaneously condenses the A minor + F major triads (known from the starting bar): it unites the tonic minor chord with its negative substitute chord (F major), as seen more clearly below: Fig. 223

This is the very moment when stage action metamorphoses into mythology: the ’sea’ becomes perceivable in its full depth. With A minor we have retraced the circle to the starting point. The first half-sentence ends with a deceptive cadence (dramaturgically, too) as it brings the process to a halt; the second half-sentence remains open on the dominant. Consequently, the C minor (b. 9) and the E major (b. 16) enter into a complementary relationship again. The main conclusion for us to be drawn from this analysis

is that Wagner uses the 12 degrees of the chromatic scale the way the dodecaphonists

used the 12 notes of the "Reihe". Each degree has its exact, logically

defined place in the row:

The modal melody exploits the potentiality of the set

of tones to the full. This is what accounts for the indivisible unity of

the theme, and first and foremost for the organic cohesion between

the tones. I am not the only one to have been struck by the ortographic

’beauty’ and tidiness of Wagner’s score (so much in contrast with the emotional

turmoil and ’debaucheries’ of the work). The analyst tends to conclude

that the score of Tristan – a coliseum of notes – could never have

been erected without the help of an infallible ’absolute pitch’. It must

be one of the many contradictions that Wagner did not have absolute pitch.

This again (i.e. the identification of any pitch in relation to

a tonal center) underpins the argument: it is the modal content of the

12 degrees in which the vital principle of Wagner’s music inheres.

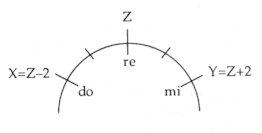

It was the introduction of the computer that brought about the most unexpected turn in these analyses. In 1983 I compiled a program, making use of the simplest combinations and permutations found in Bartók’s music. After running the program, the computer ’dictated’ — to our no small surprise — well-known melodic and harmonic passages from Tristan, Parsifal, Otello, and Boris Godunov. We must be content with some basic operations. In my programs no more than 3 numbers and 3 letters are employed. Each number or letter tells us something profoundly interesting and new about music and its perception. Number 1 indicates a perfect fifth. We mark the symmetry center of our tonal system (i.e., RE) with letter Z – while the root of the DO system is indicated by X, and that of the MI system by Y. If Z=0, then as shown in Fig. 224: Fig. 224

X = Z - 2 and Y = Z + 2 The difference between X and Y is a major third: of all the equidistant scales, the augmented triad (major third + major third) is the only one in which the number of notes (three) cannot be divided by 2! Oddly enough, the symmetry center (Z) marks the ’point of atonality’. In the axis system, besides degree RE (=Z), there is to be found one more symmetry center – and this is the tritone of RE: the SI; in C major, this is the G# (=Ab) note. In the language of geometry, we have: Z + 6 = Z – 6 Naturally, in the case of modulation (or the choice of a new key) the value of Z changes. The three notes of the major and relative minor triads show an inverted relationship: Major: X X + 1

Y

Number 1 is an important element here, because it determines the tonal character of the chord (being a perfect fifth). Both X and Y are included in the tabulation above. Number 3 expresses a modal change – according to the fact that in the axis system a modal change implies a difference of three key signatures. Let us take the simplest case: LA-DI-MI and DO-MA-SO: DI = Y + 3 and MA = X – 3 Logically, if number 3 is related to the Z center (RE), it signifies a ’dissonant’ note (=sensitive note): Z + 3 = TI

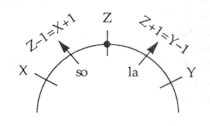

The tritonic relationship between the two notes is expressed in the difference of six perfect fifths. Note the ’outward’ and ’inward’ acting force functioning in TI and FA, respectively. It is no accident that in the subdominant D minor and dominant G major the D note (=Z) plays the role of the common note. In the subdominant chords we find a FA note (Z – 3) and in the dominant a TI note (Z + 3). Moreover, the subdominant chord involves a LA note (Z + 1), while the dominant chord a SO note (Z – 1). And because as indicated in Fig. 225 Fig. 225

LA: Z + 1 = Y - 1, and SO: Z - 1 = X + 1 we see that these two notes provide for the ’connecting link’ between Z and X on the one hand and between Z and Y on the other. That is, these two notes make the connection possible between T–S and between D–T, respectively. The formula of the positive and negative substitute chords TI - MI - SO: Y + 1

Y X + 1

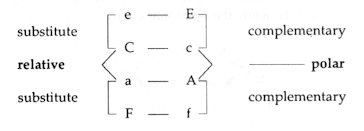

coincides with the psychological observation that we compare the former with point Y (see the role of Y and Y + 1 in the first chord) and the latter with point X (the second chord includes X and X - 1). Complementary keys express their ’annihilating’ quality in figures as well. As we know, the complementary key of C major is Ab minor — while that of A minor is C# (Db) major. In both we find the Ab (G#) note, that is, the symmetry center of our tonal system (Z + 6 = Z – 6). In the Ab minor complementary key the sensitive note TI (Z + 3) manifests itself, whereas in the C# major complementary key we find the sensitive note FA (Z – 3). The most interesting is, however, the role of the third element: in the ’negative’ complementary key (Ab minor) the MA figures (i.e., X – 3), whereas in the positive complementary key the DI plays the same role (Y + 3). * We give one single example. Let us harmonize an A minor melody with its relative major harmony, C major—and these, in turn, with their substitute chords: F major and E minor, respectively (See: Fig. 183 on p. 96). If these triads are interchanged by their parallel triads (i.e., E minor by E major, C major by C minor, A minor by A major, and F major by F minor), the symmetry remains untouched, as shown in Fig. 226. Fig. 226

The difference between C minor (with three flats) and A major (with three sharps) is six accidentals and reflects a polar opposition. On the other hand, F minor and A major are complementary

keys—annihilating each other. Similarly: E major and C minor reveal the

same relationship (the two triads result in an 1:3 model.*)

*) F minor and E major are chords with a common third - see: p.140 (ed.)

|